Federal government websites often end in. The site is secure. Engaging in a romantic relationship is a key developmental task of adolescence and adolescents differ greatly in both the age at which they start dating and in how romantically active they are. The present study describes the diversity of relationship experiences during adolescence and examines their connection to psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Latent profile analysis identified three romantic involvement groups: late starters, moderate daters, and frequent changers, which were further compared to adolescents without any romantic experiences continuous singles. Growth curve analyses indicated that continuous singles reported lower life satisfaction and higher loneliness than the moderate daters in adolescence and young adulthood. The continuous singles were also less satisfied with their life in young adulthood and felt more lonely in both adolescence and young adulthood compared to the late starters. These new forms of social relationships provide an important context to develop skills needed for future relationships, and represent a source of support, companionship, and intimacy Collins et al. Although often described as exploratory and unstable Collins et al. Due to the developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence Collins et al. The purpose of the present study is to gain a greater understanding of the variety of romantic relationship experiences during adolescence, and to study the relevance of these experiences for psychosocial adjustment from middle adolescence to young adulthood. First romantic relationships are typically established during middle adolescence, around the age of 14—15 years Collins et al. While first relationships are often of short duration, they become more stable over the course of adolescence. Seiffge-Krenke , for example, found mean relationship duration to increase between ages 15 and 21 from 5. Over the course of adolescence, most people report having had around three relationships Boisvert and Poulin Despite these general trends, there is substantial variability in when adolescents initiate romantic relationships and how romantically active they are. Differences in romantic experiences can be described by relationship patterns, which take into account multiple features of romantic involvement and consider them in combination. Multiple studies have used a person-centered approach to describe relationship patterns during adolescence Boisvert and Poulin ; Connolly et al. These studies typically find that adolescents who have dated at least once can be categorized into three to five groups based on whether they had early or late entry into their first relationship, few or many romantic partners, and little or much time spent in relationships.

Dating in the Time of Algorithms: A Comparative Analysis of Grindr and Tinder

Most previous work in this area, however, is limited in several aspects. Previous studies have often neglected the existence of the substantial proportion of adolescents who do not date at all. Excluding those who do not date results in an incomplete picture of the variety of romantic involvement. In contrast, examining more aspects of romantic involvement simultaneously would lead to a more accurate picture. In addition, number of years spent in romantic relationships might be too imprecise to assess relationship duration, especially in an age span generally characterized by short relationship duration. Months instead of years spent in relationships might be better suited to capture relationship duration in adolescence. Third, many of these studies have focused on either the first ages 12—17; Connolly et al. Finally, most studies have relied on small and non-representative samples for an exception, see Connolly et al. Engaging in romantic relationships has long been seen as an important developmental task of adolescence. Furman and Shaffer , for example, theorized that a romantic partner can serve as attachment figure that the adolescent can turn to for friendship, support, intimacy, and sexuality. Indeed, some studies point towards the benefits of engaging in dating in adolescence, as those who engage in romantic relationships report higher self-esteem in middle and late adolescence Ciairano et al. However, other theoretical approaches have suggested that dating during adolescence can have negative consequences for the well-being of at least some adolescents, proposing either early age or non-normativity as the main reason. In his theory of psychosocial development, Erikson , proposed that forming close and intimate romantic relationships is a developmental task that is more relevant in young adulthood, while identity development, instead, is the primary task in adolescence.From this perspective, a preoccupation with dating before having established a personal identity could be problematic for future adaptation and function. Romantic relationships in adolescence may also be emotionally challenging and overwhelming as they require levels of attention, communication, and problem-solving skills that may not yet be fully developed Davila This is because those who engage in behaviors earlier or later than the norm might receive more negative social sanctions and fewer social resources, which could lead to persistent developmental disadvantages Elder et al. Indeed, studies have shown that those who start dating in early adolescence show more depressive symptoms Natsuaki and Biehl , and more aggressive and delinquent behaviors Connolly et al. In addition, those who do not date at all during their adolescence experience greater social dissatisfaction Beckmeyer and Malacane and lower self-esteem Ciairano et al. In general, more studies have investigated the effect of getting romantically involved at an early opposed to a later age. Being romantically over-involved, very sporadically involved, or not at all involved could present additional risks to psychosocial adjustment. In particular, the combination of these aspects of romantic relationships i. Davies and Windle , for example, found that early age of first relationship was associated with fewer problematic behaviors when participants had fewer as opposed to more partners. Previous studies on the development of psychosocial adjustment from adolescence through young adulthood have yielded inconsistent results. Some point towards increases in self-esteem Orth et al. Lastly, some studies find no change in life satisfaction Baird et al. However, large differences in the amount and direction of change suggest a variety of trajectories that may be partly explained by the diverse relationship experiences had during adolescence. Conversely, abstaining from dating was associated with decreased self-esteem over a period of eight years in a sample of young adults Lehnart et al. Those studies that do exist have found that adolescents who reported a higher number of relationship partners and more frequent dating were more likely to show poorer emotional well-being Longmore et al. However, exactly how the development of psychosocial adjustment is affected by multiple aspects of adolescent romantic involvement is still unclear. The current study utilizes data from a large and nationally representative study following adolescents from the age 16 until 25 to address three major questions.

https://pub.mdpi-res.com/ijerph/ijerph-19-14263/article_deploy/html/images/ijerph-19-14263-g001-550.jpg?1667641975How to Create a Dating App – A Complete Guide

First, the study seeks to obtain a rich picture of the diversity of relationship experiences in adolescence. Thus, within-individual combinations of the following three aspects are examined: age of first relationship, number of romantic partners and number of months spent in relationships between the ages of 10 and Based on previous findings, it was hypothesized that those who have had at least one romantic relationship during their adolescence could be meaningfully divided into three to five groups. This study also hypothesized an additional group of adolescents who have no dating experiences. Second, the study examines whether the previously identified groups differed in their psychosocial adjustment during adolescence, and examines both problematic loneliness and depressive symptoms and beneficial life satisfaction and self-esteem dimensions of adjustment. Based on previous findings and theoretical considerations discussed in the introduction, it was hypothesized that groups characterized by either high cumulative romantic experiences in adolescence i. Finally, the study explores how these groups develop in their psychosocial adjustment through young adulthood. With limited research to guide predictions, no specific hypothesis about the impact of romantic experiences on development through young adulthood was made. However, based on the few studies that found lasting effects of romantic involvement during adolescence on later mental health, differences that were found in adolescence were anticipated to persist through young adulthood. Data were drawn from the German Family Panel pairfam Release The representative sample was drawn from register data, and participants are interviewed annually using computer-assisted personal interviews CAPI as well as self-administered computer-based assessments CASI.Participants are provided a cash incentive of 10 Euro for participating in each interview see Huinink et al. The majority of the participants Most participants were attending high school during the first wave To explore attrition effects, individuals who did not participate in the last wave were compared to those who did on psychosocial adjustment at the first assessment. No significant differences were found in neither of the aspects, indicating no systematic attrition and that data were missing at random. Romantic involvement was assessed by means of an event-history calendar EHC; Belli and Callegaro , a widely used instrument based on a graphical time frame that uses visual cues to facilitate autobiographic memory retrieval. The EHC was implemented for the first time in Wave two, where participants reported on current and past romantic relationships. This information was updated in each subsequent wave, providing a full description of their entire romantic relationship history. Based on this information, three variables were created: Age of first relationship, number of relationships, and total months spent in relationships between the ages of 10 and A variable reflecting the age of first relationship was created based on the age at which participants first reported having had a romantic partner. This variable was only calculated for those who reported having had at least one relationship by age The number of different romantic partners was calculated by adding up the number of partners listed between the ages of 10 and This variable was compiled by adding up the number of months spent in romantic relationships between the ages of 10 and 20, independent of the number of partners. Different aspects of psychosocial adjustment were assessed over multiple waves. Life satisfaction was assessed with one item adapted from the German Socio-Economic Panel i.

Emerging Adulthood

This instrument was found to be reliable with a retest reliability of around 0. Self-esteem was assessed using three items e. Johnson et al. To further ensure that the measure assessed the same construct over time, measurement invariance was evaluated. Constraining the factor loadings and intercepts for each indicator to be equal across measurement occasions i. The response format ranged from 1 not at all to 5 absolutely. Loneliness was assessed using a single item i. Response options ranged from 1 not at all to 5 absolutely. A direct single-item measure is used frequently in loneliness research and has been shown to be both reliable Zhong et al. To obtain the mean score of depressive symptoms, the items assessing positive mood were recoded. The response options ranged from 1 almost never to 4 almost always. Latent profile analysis LPA was conducted to identify groups of adolescents differing in their romantic experiences. LPA is a person-centered approach that identifies classes of individuals characterized by similar responses on a set of continuous indicator variables Nylund-Gibson and Choi In the present study, the three variables of romantic involvement were used as indicators of class membership. Participants who indicated being single during the study or who reported having had their first relationship after the age of 20 were categorized a priori into the singles group and were, therefore, not considered in this analysis. For all four statistics, lower values indicate a better model fit. When there is no global minimum, the point with diminishing returns can be used to choose the optimal number of classes Nylund-Gibson and Choi In addition, entropy was examined, where higher values indicate higher classification accuracy. Lastly, sample size of the smallest group was considered; this was done to avoid overfitting and to establish sufficient power for further analyses. Analyses were carried out with Mplus, version 7.

Why learn about development changes during emerging adulthood?

Class-specific means were freely estimated, while class-specific variances were constrained to be equal. Once the best fitting model was selected, individuals were assigned to groups based on their highest affiliation probability. To test whether the previously defined groups differed in their psychosocial adjustment in middle adolescence and in their psychosocial development through young adulthood, a series of first-order latent basis growth curve models was calculated Grimm et al. First-order latent basis growth curve models were calculated separately for each of the four psychosocial adjustment variables. For each model, one manifest indicator variable from every available measurement occasion either mean or single-item value was used. For the slope, the first slope-loading was fixed to zero and the last slope-loading to one to identify the direction and degree of change from the first to the last measurement point. The slope loadings in between were freely estimated. The variances and covariance of the latent intercept and slope factor were also freely estimated. For the manifest variables, the means were fixed to zero and variances were set to equal across all measurement occasions and variances. In order to test group differences, group affiliation was tested as a time-invariant predictor variable of the intercept and slope factor. Group affiliation was included as a dummy-coded variable with varying reference groups, so that each group was compared with one another.

The Biopsychosocial Model: Causes of Pathological Anxiety

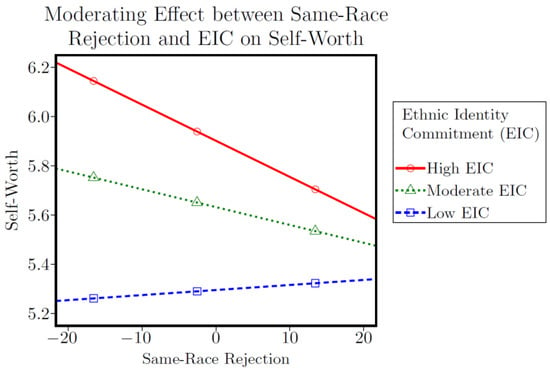

All models were calculated with a structural equation modeling approach using the lavaan package Rosseel in R R Core Team Missing values among the psychosocial adjustment variables ranged from 3. In order to use all available information to compute the model parameters, the full information maximum likelihood procedure FIML was used to handle missing data. This procedure provides efficient estimation of the parameters and is less biased than listwise deletion, pairwise deletion, or mean imputation in longitudinal research Enders Furthermore, FIML has been shown to perform well in cases with large proportions of missing data, especially when the missing-at-random-assumption is met D. Johnson and Young , which was the case in the present study. Participants who were romantically active in their adolescence reported having had their first relationship in middle adolescence, had more than one romantic relationship on average, and spent around 24 total months of their adolescence in romantic relationships. These three variables were significantly correlated with each other: The younger participants were at their first relationship, the more partners and the longer the total length of romantic involvement they reported by age The correlations regarding the psychosocial adjustment variables refer to the average values across all waves. The psychosocial adjustment variables were also all significantly correlated with each other: Both the correlations between life satisfaction and self-esteem and between loneliness and depressive symptoms were positive. In evaluating the correlations between romantic relationship indicators and psychosocial adjustment, loneliness was found to be related to two of the indicators: The later participants started dating and the more time they spent in relationships, the less lonely they felt. The model with six classes could not be properly identified, as the best log likelihood values in the model estimation could not be replicated and estimates were unreliable. Out of the remaining models, the three-class solution was chosen for the final model for the following four reasons: First, although each fit statistic decreased across the two- to the five-class solution, the smallest decrease was found when moving from the three- to the four-class solution, suggesting minimal improvement when a fourth class was included. Second, the LMR comparing the three- to the four-class model was not significant, again suggesting that a model with four classes did not fit the data better than the model with three classes. Fourth, when comparing the distribution of romantic relationship indicators in the three- and the four-class solutions, the additional fourth class was found to be conceptually redundant to one of the other three classes. After deciding on the final model, individuals were assigned to classes based on the highest affiliation probability. The entropy score for the final model indicated good classification accuracy.In addition to the three classes covering romantic involvement during adolescence, a fourth class was included for those participants who remained single during their adolescence. The final number of classes was in line with the first hypothesis. The first and largest class was labeled late starters The smallest group was called frequent changers 7. The second-largest group comprised The group of those who reported not having had a romantic relationship by age of 20 was termed continuous singles and comprised The first intercept represents the initial level of the variable at the first wave when variable was assessed. The second intercept refers to the level at the last measurement point. Slope represents change across measurement occasions. There were no other significant differences in the intercepts between the groups. The slope across measurements was significantly negative for each group, suggesting a general decrease in life satisfaction over time. Results indicated no significant group differences in either the intercepts or the slopes. Independent of group affiliation, self-esteem decreased significantly across the years. The magnitude of change in loneliness was equal in all groups and indicated a general increase in loneliness over time. In all groups, depressive symptoms increased over time through young adulthood. Together, these results suggest that part of the hypothesis regarding the link between romantic involvement and psychosocial adjustment was supported.

Online Dating in Asia: A Systematic Literature Review

In particular, those with no romantic experiences in adolescence indicated lower life satisfaction and more loneliness than those who dated moderately. However, the group characterized by frequent dating did not differ from the others in these aspects and no group differences were found in self-esteem or depressive symptoms. Regarding the exploratory question, although romantic involvement had no impact on the rate of change of psychosocial adjustment, lasting associations were found for life satisfaction and loneliness in young adulthood. Two sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the results. First, parametric bootstrapping with replications was applied to the growth curve models. The results of these analyses fully replicated those of the main analyses. Second, to ensure that findings were not sensitive to missing data, all models were further estimated utilizing solely participants with complete data. Again, the results of the main analyses were largely confirmed. All statistically significant effects found in the main analyses were fully replicated. Overall, the results of these sensitivity analyses largely replicated the main findings. In the following section, only the robust results of the main analyses will be discussed. Finally, it should be noted that all data analyses were conducted as planned and no participants or variables were excluded due to lack of significance.Romantic relationships represent a new and developmentally important context for adolescents Furman and Shaffer However, not all adolescents have the same romantic experiences and there is large variation in the age at which adolescents first start dating and how romantically active they are Collins et al. Further, those characterized by either being overly romantically involved or by having little to no relationship experience may be especially prone to experiencing poorer adjustment in both adolescence and young adulthood. Using data from a German representative longitudinal study, the current study identified four groups of adolescents based on their romantic involvement between the ages of 10 and 20 and tested whether they differed in their psychosocial adjustment from middle adolescence through young adulthood. These four groups included late starters, moderate daters, frequent changers, and continuous singles. The continuous singles reported lower life satisfaction and higher loneliness compared to the moderate daters and late starters. This effect was not only evident in middle adolescence but remained over a period of 10 years through young adulthood. Although both scholars and lay culture often assume adolescent romantic relationships to be short and trivial, these findings suggest great variability in romantic relationship experiences with regard to the age when adolescents first get involved, how many partners they have, and how much total time they spend in these relationships. Late starters and moderate daters were similar in their group sizes and represented the largest groups, whereas only a few adolescents were categorized as frequent changers. Most adolescents started dating in middle and late adolescence, had around one to two different partners, and were romantically involved for a total of around 14 to 34 months. By using multiple indicators of romantic involvement as well as covering the whole period of adolescence from early to late adolescence in a large and representative sample, the current study replicates and augments the findings of previous studies Boisvert and Poulin ; Connolly et al.

Chapter 24: Psychosocial Development in Early Adulthood

The period of adolescence seems to be marked by great variability in relationship experiences, and including those who did not date at all during their adolescence showed that a substantial proportion of adolescents are not romantically active in their youth. Previous findings regarding romantic involvement during adolescence and its effect on psychosocial adjustment have been mixed, stressing both risks and opportunities. Out of the four investigated aspects of adjustment, group differences were found in two: Moderate daters reported higher life satisfaction than the continuous singles in middle adolescence, and both moderate daters and late starters felt less lonely than the continuous singles in late adolescence. That the moderate daters and late starters indicated better adjustment than the continuous singles at least in some aspects was in line with the hypothesis, as both groups could be assumed to represent groups of adolescents with normative relationship experiences with regard to age of first romantic experience and overall romantic involvement as compared to the abstaining group. The differences found in life satisfaction and loneliness could reflect the social nature of romantic involvement. For many adolescents, dating is a way to achieve social status and validation from peers Carlson and Rose , and having a romantic partner has been identified as a consistent factor shielding against loneliness Luhmann and Hawkley Those who remain single during their adolescence might feel as though they are missing out on these pleasant and enriching social experiences, which could make them less satisfied with their lives and more prone to feeling lonely. Self-esteem and depressive symptoms, on the other hand, were entirely independent of relationship experiences during adolescence. Both loneliness and life satisfaction may therefore represent more context-dependent aspects of psychosocial adjustment that are more easily affected by changes in relationship status. It is important to note at this point, however, that psychosocial adjustment was assessed first in middle to late adolescence. It could be that continuous singles were already less satisfied and more lonely in childhood and early adolescence, which could have prevented them from engaging in a romantic relationship in the first place. The lack of differences between the other groups of romantically active adolescents was surprising. Based on the theoretical frameworks outlined in the introduction, as well as previous findings showing that early age of first initiation Connolly et al. The frequent changers were also likely to having experienced the most break-ups compared to the other groups, an event that has been found to be a prospective risk factor for psychological distress Rhoades et al. The authors offer two possible explanations for the lack of group differences concerning the frequent changers: First, compared to findings of previous studies, frequent changers initiated dating at a later age i. Second, although frequent changers experienced more relationship dissolution than their peers, their relationships were also likely to be of short duration and of lower commitment, which may have alleviated the impact of each breakup on mental well-being. These explanations are, however, speculative, and should be explored in further research. The group differences found in adolescence were also present in young adulthood, with continuous singles reporting lower life satisfaction and higher loneliness than the moderate daters. In young adulthood, additional group differences emerged: While late starters did not differ in life satisfaction from continuous singles during adolescence, they reported higher life satisfaction in young adulthood.There were no group differences regarding the rate of change in any of the adjustment variables. Together with previous findings showing a normative trend of decreasing life satisfaction Goldbeck et al. This could be, at least in part, explained by the many developmental challenges that adolescents face during this time, including biological, cognitive, social, and academic transitions Steinberg , and calls for further investigation concerning potential risk and protective factors that go beyond the field of romantic involvement. Together, the analyses of the current study provide compelling evidence that getting romantically involved is a normative event during adolescence and that there is great variability in the romantic experiences adolescents have. Further, a substantial proportion of adolescents do not date, and the present findings highlight the importance of taking into account this often ignored group when examining romantic relationship patterns. Continuous singles are particularly interesting, as they seem to differ from all other groups with regard to some aspects of psychosocial adjustment both in adolescence and through young adulthood. It should be noted, however, that although singles indicated lower life satisfaction and more loneliness than the other groups with small to moderate differences 0. Nevertheless, these differences may have significant long-term consequences for well-being. These findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, although the study covered romantic relationship experiences starting at age 10, the first assessments of psychosocial adjustment took place in middle to late adolescence age 16— This asynchronous design implies limits regarding causal interpretation of the results. Future research should assess both romantic involvement and adjustment beginning in early adolescence to disentangle possible selection and socialization effects of romantic relationships. Second, loneliness and life satisfaction were assessed using single-item measures and self-esteem with an abbreviated measure consisting of three items. Future studies should therefore replicate the current findings with multi-item measures. Third, some of the information on romantic involvement was assessed retrospectively, as adolescents reported on both current and past relationship experiences.

Votre commentaire: